Who invented playing cards? The history of the 52-card deck

History of the 52-card deck in a nutshell

Playing cards were invented in China between the 9th and 13th centuries AD. From there, they spread to Persia and Muslim Egypt, eventually reaching Europe through the Iberian Peninsula in the 14th century. The first European cards—the Latin-suited cards—were based on the Arab (“Moorish”) deck. By the 15th century, new local patterns and decks had been invented in various regions of Europe, and around 1480, the French borrowed some of the German features to create a 52-card deck of cards optimized for cheap production. In the 19th century, British and American cardmakers modernized the French playing card design to enhance the players’ comfort and the cards’ durability. This led to the creation of the Anglo-American 52-card deck, which is now the most popular playing card deck worldwide.

Popularized by games like Contract Bridge, Poker, and online solitaire, a deck of 52 cards is the most widely used by players around the world. The deck consists of two black suits, Clubs (♣) and Spades (♠), and two red suits, Diamonds (♦) and Hearts (♥). Each suit comprises three face cards—King, Queen, and Jack—and ten numerals, also called pip cards, ranging from one (Ace) to ten. The corners of the cards are slightly rounded, with an index showing a suit symbol and the number of pips (2–10), or an initial letter for face cards (K, Q, and J) and the Ace (A). All the cards are reversible (i.e., double-headed), and the face cards show only the upper torsos and heads of the court members. The pip cards indicate their numerical values by displaying the corresponding number of the suit symbols (Figure 1). Have you ever wondered how and when all these features came together? Who invented playing cards? Where do the suit symbols come from? Why does the Jack accompany the King and Queen? This article answers these questions and more by exploring the history of the Anglo-American 52-card deck.

The origin of Chinese playing cards

People have always liked to entertain themselves, even in the most ancient times, so we are not much different from our ancestors in this respect. It is pretty exciting to think that on our game nights, we still repeat the same gestures our great-great-etc.-grandparents made thousands of years ago in India when they rolled their first six-sided die (Figure 2) – the oldest predecessor of a playing card. Dice made their way to China perhaps as early as the 2nd century BC, where more than a thousand years later, some inventive player joined two dice together to form a domino tile. Once the form of a tile was in place, it was only a matter of time before it was made from paper and turned into a card.1

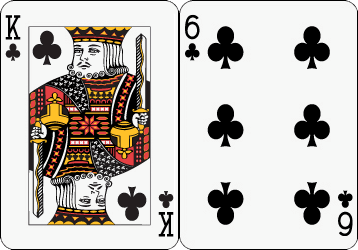

When Westerners think of cards, they automatically assume they are made of paper. But in Chinese games, the material of the “tile” was not that important. Many games, including dominoes, could be played with “tiles” made of bone, ivory, or paper, which are even described by the same term in modern Chinese: pai (zhi pai meaning “paper tiles,” i.e., cards).2 Of the materials used to produce Chinese “tiles,” paper is one of the most perishable. Perhaps this is why the oldest Chinese paper card (Figure 3), discovered in 1905 near Turfan in north-western China by a German archaeologist, Albert von Le Coq, is only known to date back to as late as ca. 1400 AD.3 However, many scholars believe playing cards were invented even 500 years earlier, in the 9th or 10th century.4

But were they really? The primary evidence supporting this theory is Xiu Ouyang’s description of the 9th-century Tang dynasty “game of leaves” (葉子).5 Xiu, an 11th-century historian, explains that in the Tang period, the most common form of a Chinese book was a scroll. However, this form would become extremely inconvenient when constantly referring to notes made while playing. To avoid long pauses, during which a player would unroll the entire scroll to look up the necessary information and then roll it back up again, the Chinese invented a form of a reference book similar to a contemporary notebook. Its pages were called yèzi, “leaves,”6 and many scholars interpreted them as playing cards. Andrew Lo, however, disagrees, suggesting that the 9th-century yèzi refers only to pages of a reference book used to play a board game known as “the game of leaves.” He also points out that the earliest occurrence of the confirmed and still used term for “paper playing cards,” zhi pai (紙牌), comes from a 1294 lawsuit recorded in the Dynastic Code of the Sacred Administration of the Great Yuan Dynasty, completed in 1320.7 And these dates bring us much closer to the 14th-century Turfan card than to the alleged 9th-century origin of playing cards.

The question of when the Chinese invented their playing cards rests on an interpretation of the Tang Dynasty term yèzi. If it refers to “playing cards,” then their invention dates back to the 9th century. But if it means “book pages” instead, then we can trace back the earliest known form of Chinese playing cards only to the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Egyptian playing cards of the Mamluks

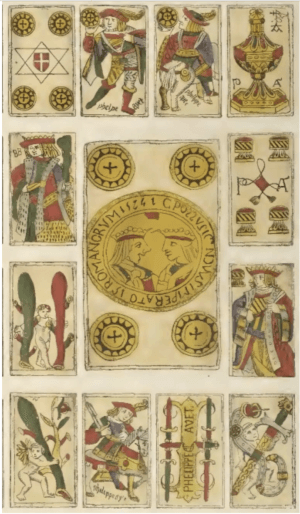

Very little survives of the earliest playing cards of the Muslim world. The Keir Collection, currently in the Dallas Museum of Art, holds two fragments of numerical cards whose style points to 13th-century Egypt. The cards belong to a suit that may seem exotic to a player familiar only with Anglo-American playing cards – the suit of Cups, symbolized by exquisite chalices (Figure 4).8 This design originated during a tumultuous time of power shifts when, amidst the chaos of the 7th Crusade, the Ayyubid dynasty that had ruled Egypt ended. In 1250, the Egyptian sultanate passed to the former slave warriors of the Ayyubid, the Mamluks, who ruled Egypt until 1517.

Toward the end of its reign, the Mamluk Sultanate produced the best-preserved deck of early Arab playing cards that exists to this day. These so-called “Mamluk cards” are dated to the 15th century, although they include five cards that could be of earlier or later date.9 The cards (Figure 5), which are held at the Topkapı Palace Museum in Istanbul, have sparked the interest of some historians, who see them as a possible link between the Chinese and European playing cards because of their similarities to both types. The Topkapı deck originally consisted of 52 cards (of which only 48 have survived) divided into four suits – Coins, Polo Sticks, Cups, and Swords. Each suit has ten numerical and three court cards: the King (malik), the Viceroy (nā’ib mālik), and the Second Viceroy (thānī nā’ib).10

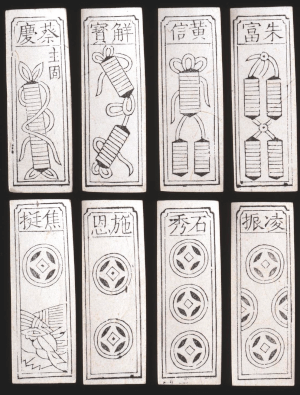

One of the Chinese decks, the so-called “money-suited cards,” which was first described in the 15th century, also had four suits (but the difference was that it did not include court cards): Coins (or Cash, i.e., Chinese coins pierced in the middle), Strings of Cash, Myriads of Strings, and Tens of Myriads (Figure 6).11 Some authors hypothesize that the Mamluks may have reinterpreted Chinese suit symbols to create their own set.12

However, there are two arguments to the contrary:

1)The 13th-century Mamluk cards in the Keir Collection are 200 years older than the oldest examples of their presumed Chinese ancestor.

2)Both the Topkapı pack and the Arabic texts of the time refer to playing cards with the term kanjifah borrowed from the Persian language.

Therefore, it seems most likely that playing cards traveled from China to Persia before entering the Arabic-speaking world.13

Arabs have known playing cards since at least the 13th century; such is the date of the earliest surviving Egyptian cards. Playing cards came to Egypt from Persia, and the Persians derived their cards from the Chinese model.

The first European playing cards

The earliest, albeit very brief, reference to playing cards in Europe comes from a rhyming dictionary compiled in Catalan by the poet Jaume March in 1371. It is just one word, naip, which is still used in Catalan for “playing cards”14 and was most likely derived from the Arabic nā’ib (نَائِب), meaning “deputy.” Interestingly, nā’ib occurs in the names of two court cards in the Mamluk Topkapı deck: Viceroy (nā’ib mālik) and Second Viceroy (thānī nā’ib). It is easy to imagine that the 14th-century Catalans first used this Arabic term to refer only to the court cards and then gradually began to apply it to talk about the game or the cards in general. Nevertheless, the use of the cards-related term nā’ib in medieval Catalonia has two profound implications:

1)Europeans must have adopted playing cards from the Arabic-speaking peoples.

2)Topkapı-like decks must have been produced by the Arabs as early as the 14th century, although we have no material evidence of 14th-century court cards.

An entry in the chronicles of the Italian city of Viterbo reveals that 14th-century Italians were aware of the Arab provenance of playing cards. An anonymous chronicler notes that “In the year of the Lord 1379, there was brought to Viterbo the game of cards, which in the Saracen [i.e., Arabic] language is called nayb”.15

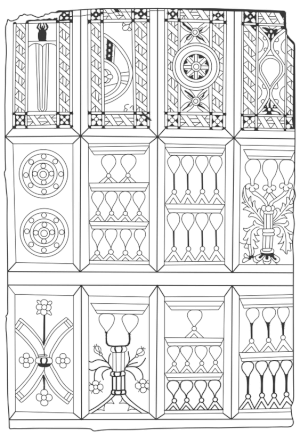

So, did Europeans bring playing cards directly from the Mamluk Egypt? It seems more likely that the point of contact was the Iberian Peninsula,16 which, from the 8th to the 15th century, was under the (gradually diminishing) rule of the Arabs, called “Moors” by the Europeans of the time. The region of Iberia, with its long-standing and close ties to the Arab world, was a natural gateway through which every practical and desirable innovation entered Europe. Like the oldest textual evidence for playing cards, the oldest actual cards discovered on European soil also come from Catalonia – Simon Wintle, a card history enthusiast, found them among the holdings of the Institut Municipal d'Història in Barcelona, where they had been lying for decades, unknown to a broader public. It is an uncut sheet of uncolored cards from the early 15th century, made after the Arab design. The original from which the cardmaker copied the suit symbols, probably featured polo sticks instead of clubs. However, due to the lack of familiarity with polo in the Christian world, the artisan reproduced them without realizing their true meaning (Figure 7).17

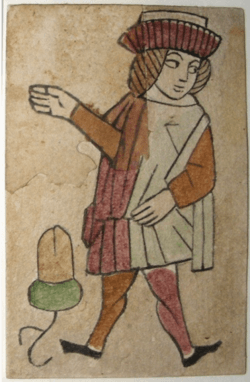

Once Catalans and Italians got hooked on playing the “new” game, the cards spread like wildfire across Western Europe. Historical sources first mention playing cards in the 1370s in Florence and Siena (Italy), Paris (France), Basle (Switzerland), and the province of Brabant (Belgium), with the number of references multiplying over the next two decades.18 Europeans almost immediately began producing their cards, experimenting with designs and deck compositions, and gradually developing regional suit systems that are still used today. The first was the Latin system (used in Spain, Portugal, and Italy),19 an early example of which is another Catalan “Moorish” deck, dated 1400–1420 and held at the Fournier Museum of Playing Cards in Álava, Spain (Figure 8). It preserves the Arab suit symbols – Coins, Cups, Clubs, and Swords. It also shows human figures in different positions: standing, seated, or mounted. This is in contrast with the Topkapı playing cards, which did not depict King, Viceroy, and Second Viceroy as human figures, but only identified them through inscriptions. The visual representation of people was a milestone in the history of playing cards, marking the transition from the originally Arab design to the Anglo-American deck that is widely used today.

Playing cards came to Europe before 1370 from the Arab world through Spain. The Latin deck was the first original European card system. It preserved the Arab suit symbols (only replacing the Polo Stick with the Club) but introduced human figures on court cards.

History of modern playing cards: the French system

Our story now quickly approaches its culmination – the creation of the Anglo-American pattern, which has made a worldwide career. It originated from the French-suited cards invented in the 15th century. In contrast to the history of playing cards in earlier ages, 15th-century Europe has left us with a wealth of textual and material evidence. Interestingly, most of the playing cards from this period known today have survived because they were downcycled to reinforce bookbinding.20 Such discoveries provide one more reason to read old books!

In the 15th century, Europe saw the emergence of numerous regional decks of cards, including the Spanish, German, and French decks. We will discuss them one by one.

The Spanish deck was created by the French. For most of the 15th century, the French manufacturers produced Latin-suited cards for the Spanish market, at the same time slowly modifying the Latin deck. By 1460, they had simplified the design of the cards and replaced the traditionally seated Kings with standing ones.21 Eventually, they created what is now known as Spanish-suited playing cards:

•suit symbols preserved from the Arab deck (Coins, Clubs, Cups, and Swords);

•three cards picturing members of the medieval royal court: a standing King, a mounted Cavalier or Knight, and a standing “servant” or “young man” – Knave;

•nine pip cards with the numbers from 1 to 9;

•a total of 48 cards in a deck (Figure 9).22

Around the same time (ca. 1460), after several decades of experimenting with various decks and suit symbols (among the most popular, those related to hunting; Figure 10), Germans finally established their standard deck. They settled on suit symbols that differed from the Latin and thus from Arab ones: Leaves, Hearts, Acorns, and Bells.23 Nevertheless, as in the Latin (and, even earlier, the Arab) original, there were also three male court cards in the German system: the King and two Knaves – the Ober (Overlord) and the Unter (Underling) (Figure 11). All the figures held their suit signs in their hands, and the Knaves were distinguished by whether they pointed their hands up (the Ober) or down (the Unter). The deck consisted of 48 cards, but unlike the Spanish, this one included the ten-pip card instead of the one-pip card (the Ace).24 The Spanish and German decks have been used in their respective regions in a relatively unchanged form to this day – they are the remnants of the earliest European playing cards.25

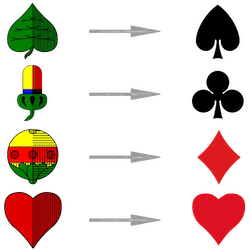

Finally, by 1480, the French were ready to develop their own deck, intending to produce cards as quickly and cheaply as possible. Their experience with the Spanish symbols showed that they were too complicated to draw and color with stencils – the preferred method of illustrating cards of the time. Therefore, the French adopted the German suit symbols but standardized their shape, size, and color. Leaves became Spades, Acorns turned into three-leafed clovers – Clubs, Bells somehow reshaped into Diamonds, and Hearts just stayed Hearts (Figure 12). The standing King, which the French cardmakers had invented for the Spaniards, and the Knave were fine. Still, the mounted Cavalier was too complicated to draw. Simultaneously, the German Ober and Unter were so alike that the players could not tell them apart at first glance. These problems with male court cards opened the door for the standing Queen. The Queen was also a German invention, but it had appeared in alternative decks with four court cards as an equal to the King and superior to the Ober and the Unter. It replaced the Cavalier in French decks, leading to the combination: King, Queen, Knave. Their suit symbols simply floated in the air (Figure 13) rather than being held by court members as in previous designs.

All these changes allowed the French cardmakers to return to the original composition of a hand-painted Arab deck: 52 cards with three court cards and ten pips per suit. The 52-card decks were not unknown in medieval and early Renaissance Europe – in fact, the only surviving complete 15th-century deck, the Cloisters set, is of this type. However, with the advent of printing and the woodblock printing technique in particular, manufacturers began to favor decks of 48 cards. Woodblocks were large wooden stamps with card designs carved on them. The artisan would cover these stamps with ink and press them onto paper. This way, it was easy to make 24 cards on a rectangular block (in six rows, four cards per row), but distributing 26 cards on the woodblock was impossible! Any attempt to print 52 playing cards would result in an overproduction of twenty unneeded cards, inevitably increasing production costs. Moreover, the different shapes and sizes of the suit symbols required multiple coloring stencils. In a stroke of genius, the French limited printing to just court cards – there were 12 of them per deck, which fit nicely on a single woodblock. With the standardization of suit symbols, the pip cards could now be made by simply stamping the card with a single stencil, eliminating the need for printing. Thus, French production became faster and more economical, revolutionizing the European card market.26

Most of the features of the modern Anglo-American deck were introduced by the French cardmakers around 1480: a deck of 52 cards, with the suits of Spades (♠), Clubs (♣), Diamonds (♦), and Hearts (♥), and the Queen as one of the three court cards. The main reason for these innovations was to optimize production.

The most popular playing cards: Anglo-American pattern

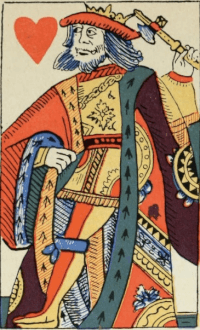

A standardized modern 52-card deck invented by the French needed only a few final tweaks to become the playing cards used in online and offline games around the world today. In the 15th and 16th centuries, one of the markets for French-suited cards produced in the city of Rouen was England, and it was the British who were responsible for transforming the cards’ design by the 18th century. The first change was unintentional. With less experience in the craft, the design quality declined, and some details introduced by the French artists were misinterpreted and distorted.27 Compare the King of Hearts, made in Rouen around 1567 (Figure 14), with its British equivalent made around 1750 (Figure 15). Aside from the artistic values of the latter, the figure has no legs, and instead of wielding an axe, it appears to be sticking a sword into its head. Funnily enough, the King of Hearts still does this in the 21st-century Anglo-American deck (Figure 16), for which he has earned the nickname “Suicide King.”

Most of the British innovations, however, arose from the practical needs of the cardplayers. At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, British cardmakers slowly began to adopt a recent French novelty of reversible (i.e., double-headed) cards. Players would no longer have to flip their court cards, which had been a blatant tell to their opponents.28 Another problem for the players had always been that they couldn’t see the cards’ values when holding a card fan. This was due to the lack of corner indices. Although indices consisting of two elements—the suit symbol and the rank—had been known in Europe since the 15th century, it was not until 400 years later that they were placed in the corners of cards. The American cardmaker Cyrus W. Saladee introduced corner indices in 1864, and the most influential playing card manufacturers in England, Goodall and Son, did so in 1874.29 Goodall and Son are also responsible for the facial features of 21st-century Anglo-American court cards.30

It was not long before the Americans, led by Samuel Hart and his company, the New York Consolidated Card Co., overtook the British as the leading card producers. Hart came up with the idea of rounding the corners of playing cards so they would not wear out too quickly.31 In 1864, he observed that the abbreviation Kn for Knave (which in a few years was to make it to the corner index) was easily confused with K for King. Hence, Jack came into being as Hart replaced Kn with the abbreviation J for the English word “jack.” This was not a new term for the Knave, as it had been used in the 17th century in the card game All Fours, but it was considered vulgar at the time. By the 19th century, however, “jack” had lost its pejorative connotation in the U.S. and was used to refer to a generic male, making it somewhat synonymous with the original meaning of “knave” – “boy or young man.”32

Finally, Hart also invented another famous card: the Joker,33 but this part of the story goes beyond the 52-card deck.

In the 20th century, woodblock printing was long gone – the cards were now coated with plastic to strengthen them. Refreshed by the British and Americans and produced on mass scale, the French-suited cards set out to conquer the world. The incredible popularity of Poker, Rummy, and Contract Bridge pushed aside other European and Asian decks but, fortunately, did not wipe the traditional decks out. China, India, Spain, Germany, and many other countries still cultivate traditional games and unique card designs.

The modern Anglo-American pattern of playing cards came together in the 19th century through innovations by British and American cardmakers. Based on French-suited cards, they introduced a double-headed design and rounded corners with the indices and changed the name of the lowest court card from Knave (Kn) to Jack (J).

References

- ^ Wilkinson 1895: 67, 77; Needham 1962: 328–331.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 35.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 38.

- ^ E.g., Needham 1962: 329; Dummett 1980: 34.

- ^ I thank Adrian Kędzior for helping me out with the Chinese sources.

- ^ https://www.gutenberg.org/

cache/epub/25431/ .pg25431.html - ^ Lo 2000: 403, 406.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 40n22, 41.

- ^ Dummett and Abu-Deeb 1973: 107.

- ^ Dummett and Abu-Deeb 1973: 107–108, 112; Dummett 1980: 39.

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Chinese_playing_cards# .Money-suited_cards - ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Playing_card_suit# .Origin_and_development_ of_the_Latin_suits - ^ Dummett 1980: 43–44, 57–64.

- ^ Denning 1996: 14.

- ^ Dummett and Abu-Deeb 1973: 113–114.

- ^ Denning 1996: 16.

- ^ https://www.wopc.co.uk/

spain/moorish/ .moorish-playing-cards - ^ Dummett 1980: 10; Denning 1996: 16.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 16–17.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 13.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 22–23.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 5–7.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 16, 22.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 5–8.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 27.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 23.

- ^ https://i-p-c-s.org/

pattern/ps-48.html . - ^ Dummett 1980: 11, 27n36; Laird 2009: 290.

- ^ Dummett 1980: 11, 20, 27n36; https://www.wopc.co.uk/

goodall/chas-goodall- ; https://www.wopc.co.uk/and-son-1820-1922 playing-cards/ .corner-indices - ^ https://www.wopc.co.uk/

goodall/chas-goodall- .and-son-1820-1922 - ^ https://familytreemagazine.com/

history/history-matters- .playing-cards/ - ^ Laird 2009: 290; https://www.etymonline.com/

word/jack ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_(playing_card) . - ^ Laird 2009: 290.

Cited works

Benham, W. Gurney. Playing Cards: History of the Pack and Explanations of Its Many Secrets. London: Spring Books, 1931.

Denning, Trevor. The Playing-Cards of Spain: A Guide for Historians and Collectors. London: Cygnus Arts, 1996.

Dummett, Michael. The Game of Tarot: from Ferrara to Salt Lake City. London: Duckworth, 1980.

Dummett, Michael, and Kamal Abu-Deeb. “Some Remarks on Mamluk Playing Cards,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 36, 1973, pp. 106–128.

Laird, Jay. “History of Playing Cards” in Encyclopedia of Play in Today’s Society, ed. Rodney P. Carlisle, vol. 1. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2009, pp. 288–293.

Lo, Andrew. “The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 63(3), 2000, pp. 389–406.

Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology, part 1: Physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Wilkinson, W.H. “Chinese Origin of Playing Cards,” American Anthropologist A8(1), 1895, pp. 61–78.

Figures

- Modern Anglo-American playing cards: the King and 6 of Clubs.

- Terracotta dice from Mohenjo-daro (Pakistan), 2500–1900 BC. Photographed at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford by Zunkir, image cropped. Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

- The oldest Chinese paper card from Turfan (China), ca. 1400 AD; currently at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

- Two fragments of Egyptian playing cards from Cairo (Egypt), early 13th century; currently at the Dallas Museum of Art, the Keir Collection. © 2021, Dallas Museum of Art, objects K.1.2014.1132 and K.1.2014.1133.

- 6 of Coins, 10 of Polo Sticks, 3 of Cups, and 7 of Swords cards from the Egyptian Mamluk deck, 15th century; currently at the Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul. Original composition by Countakeshi. Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

- Chinese money-suited cards, 19th century; currently at the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- The oldest European cards from Catalonia, early 15th century. An uncut and uncolored sheet of Arab design; currently at the Institut Municipal d'Història in Barcelona. Re-drawn by Karolina Juszczyk after the illustration in Simon Wintle’s “Moorish playing cards.”

- Knave of Coins from a Catalan “Moorish” deck, 1400–1420; currently at the Fournier Museum of Playing Cards, Álava (Spain). Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

- An uncut sheet of Spanish-suited cards, 1574. Originally published in Museo español de antigüedades, vol. 3, 1874. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

- Overlord (Ober) of Ducks from the Stuttgart hunting deck, 1429; currently at the Württemberg State Museum, Stuttgart (Germany). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. © Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart.

- Underling (Unter) of Acorns from a German-suited deck, ca. 1540–1560; currently at the Württemberg State Museum, Stuttgart (Germany). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. © Deutsches Spielkartenmuseum, Leinfelden-Echterdingen.

- Evolution of suit marks from the German to the French suit system. Drawing by Karolina Juszczyk with the use of images created by Infanf: Leaf, Acorn, Bell, and Heart, available through Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

- An uncut sheet of French-suited playing cards, printed in Rouen by Valery Faucil ca. 1516; currently at the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- King of Hearts from a French-suited deck, produced in Rouen ca. 1567. Benham 1931: 28, fig. 59.

- King of Hearts from a French-suited deck, produced in England ca. 1750. Benham 1931: 28, fig. 60.

- Modern Anglo-American King of Hearts.